We are a School of inquiry, innovation, and impact. Grounded in Christian values, we prepare all students to be college ready, globally competitive, and engaged citizen leaders.

How are you studying your own school? In what ways are you being a student of your own school?

Certainly you send folks to conferences like bees sent to collect pollen. It’s likely that you send faculty to other schools to learn from their practices, too. Incredible stories continue to emerge from systemic school visits (see bullets below). Of course, there are countless virtual opportunities, as well. All of these techniques are critical parts of professional learning, for sure.

- Julie Wilson, Institute for the Future of Learning, “Hitting the Road” School Visits & Site Visit Observation Field Guide

- ParkDay Tom Progressive Schools Tour

- Grant Lichtman’s #EdJourney – category of posts archiving his 2012-13 visit to more than 80 schools. And Grant’s TEDx talk about #EdJourney

But how are you ensuring you have an effective “honey production” capacity, back at school, with all of that pollen you are collecting? Are the bees only set up in their own relatively isolated honey-production facilities (“classrooms”), or are you intentional about connecting those glorious hexagons into a fully optimized honeycomb (“learning community”)? How are you tapping the wisdom and experience of your faculty as they intentionally live at the nexus of research and practice?

MVPS Norms Promote Productive Postures

At Mount Vernon Presbyterian School and the Mount Vernon Institute for Innovation, we are intentional students of our own school. As a School of inquiry, innovation, and impact, we are as purposeful about living out those qualities in ourselves as adults as we are about nurturing them in our student learners. And that makes all the difference.

Our norms empower us in numerous ways to take on this work and define the postures to help us collectively succeed:

- Start with Questions

- Fail Up

- Assume the Best

- Share the Well

- Have Fun

From such postures and commitments to inquiry, innovation, and impact, we study ourselves in a number of systemically connected ways. Two primary methods include learning walks and instructional rounds.

Learning Walk and Instructional Rounds

design as changing existing situations into preferred situations

Mount Vernon is a community of educational designers. Consequently, we feel emboldened to use design to intentionally and purposefully change existing situations into preferred situations. As designers and design thinkers, we create and employ various auto-ethnography tools to help us meet the actual needs of the users for whom we are designing. These tools help us in optimizing our honey production.

Learning walks provide us with broad surveys of our teaching and learning ecosystem. Instructional rounds provide us with deeper dives into our pedagogical practices. And our particular brand of learning walks and instructional rounds enable us to map our learning operations as a school.

- Shelley Clifford, Head of Lower School, shares practice of learning walks with parents

- The “MVPS Learning Walks and Instructional Rounds” primer document, available on Scribd and embedded below, gives an overview of these integrated practices at Mount Vernon. At the bottom right-hand corner, you will find some additional resources linked, so that you can explore things more fully. Below the embedded Scribd document, there is a link to Bo’s Diigo library list for “Instructional Rounds,” as well as a Twitter archive of a winter #ISEDchat on instructional rounds, moderated by Chip Houston.

- Bo’s Diigo library list for “Instructional Rounds”

- Chip Houston moderates #ISEDchat on Instructional Rounds – see the archive

Innovating Instructional Rounds –> Pedagography

At Mount Vernon, we are innovating the practices of learning walks and instructional rounds. Learning walks have been a part of the MVPS culture for awhile.

- Sample of #MVPSchool #LearningWalk Tweets on Storify

This year, though, we began piloting new iterations of prototypes for learning walks, and we added instructional rounds to our repertoire. Almost immediately, we started to innovate instructional rounds beyond how they exist at any other school.

In the Middle School, our Heads of Grade identified a wildly important goal for themselves, and they worked with the Head of Middle School Chip Houston, the Director of 21C Teaching and Learning Katie Jones, the Director of the Center for Design Thinking Mary Cantwell, and me (the Chief Learning and Innovation Officer) to establish a system of observing each other for intensive feedback and discussing the feedback to develop practice.

- “Instructional Rounds: An Experiment in Coaching and Feedback for Educators” by Chip Houston on Chip Houston

- “Observation + Reflection: Making Instructional Rounds Meaningful” by Alex Bragg on Bragg-ing About Education

We relied heavily on the instructional rounds work of Elizabeth City and Richard Elmore, we threaded in Japanese lesson study, and we also incorporated a mapping project into our IR work. While observing, we committed to collecting data that would allow us to more accurately map our teaching and learning core, just like Lewis and Clark mapped the Louisiana Purchase with the Corp of Discovery, or just like Google is working to map the Earth. We call this learning-culture mapping “Pedagography,” which is derived from work I initiated and led at Unboundary called “Pedagogical Master Planning.”

- Pedagogical Master Planning – category of posts on It’s About Learning

- PMP Classroom Capture Tool for Discovery (developed at Unboundary)

- PMP Booklet (developed at Unboundary)

As a team of eight, we embarked on a journey of engaging in pedagography. Chip, Katie, Mary, and I served as the first four-person observation team for the Heads of Grade – Stephanie Immel, Maggie Menkus, Amy Wilkes, and Alex Bragg. During the visits, we collected narrative notes that draw on clinical observation as a methodological basis. These notes are reviewed by the observed teachers, and the recordings serve as the lenses through which we reflect on practice and debrief as a team. These Middle School Heads of Grade pioneered this new approach to instructional rounds and pedagography, and they provided invaluable insights into the development of the practice.

To conduct a thorough pedagography, in addition to the narrative notes field, we use a number of other capture prompts that we aggregate over time to help us see more holistically our teaching and learning ecosystem. Currently, we call the entire Survey Monkey tool “Proto 3,” and we are in the process of iterating to Proto 4.

Survey Monkey Tool – Proto 3

Expanding the Instructional Rounds Practice

After tremendous first-semester work among the #MVMiddle Heads of Grade IR Pilot Team, Houston decided to expand the practice to a widened circle of educational innovators. Leveraging the experience of the pilot team, additional Middle School faculty were engaged in another start-up of the pedagography experiment.

- “Feedback from Instructional Rounds: New Network” by Chip Houston on Chip Houston

Additionally, we decided to expand the work into another division, as well. Head of Lower School Shelley Clifford and Director of 21C Teaching and Learning Nicole Martin pulled their Think Tank and Heads of Grade into the instructional rounds + pedagography. Like ripples in a pond, more teachers were being invited into this honey-production capacity building.

Conducting the Instructional Rounds Debrief

For the initial pilot of instructional rounds in the Middle School, we made the decision to jump in and get started immediately. Whereas some schools spend months prepping and training for new initiatives, Mount Vernon thrives in a “lean start-up” and entrepreneurial energy, and we believe in shipping innovations and learning by doing and iterating.

In the fall, the debriefs of the instructional-rounds observations were relatively unstructured, and we experimented with various methods for debriefing as we evolved the experiment. We learned a great deal from those debrief sessions, in terms of our meta-cognitive approach, and we applied that learning to the Lower School expansion.

For the Lower School, we started the debriefs as we did in the Middle School – the observed teacher reviewed the field notes and began the first debrief by thinking aloud about the notes and observations. Quite rapidly, though, we’ve moved to a developing protocol that asks the observed teacher to highlight the key reflections in the narrative and prepare a problem of practice objective to dig into during the debrief. Because of the hour-long time frame of the debrief and the need to discuss multiple observations, we focus each teacher debrief at about 10-15 minutes. Most recently, we’ve added “chalk talk” to our debriefs, and we systemically review the dynamic of the curriculum, instructional methods, learning space setup, and student engagement.

- “INSTRUCTIONAL ROUNDS, THE DEBRIEF” by Shelley Clifford on Visible Reflections

- “INSTRUCTIONAL ROUNDS DEBRIEF, TAKE 1” by Shelley Clifford on Visible Reflections

The Lower School Heads of Grade – Eileen Fennelly, Sherri Kirbo, Andrea McCranie, Chris Andres, and Jenny Farnham – have been an amazing team of rounders and pedagographers, especially in the ways that they are accelerating the protocol advancement of the debriefs.

What has also been profoundly rewarding is a bit of serendipity. At the same time that the Lower School was taking on the instructional rounds piloting, they also launched three book-study cohorts focused on Carol Dweck’s Mindset. As we jumped into more intensive feedback surrounding the instructional rounds practices, we found it incredibly helpful to also be studying the growth mindset as an entire division of faculty making honey together.

Beginning to Explore the Pedagography Maps

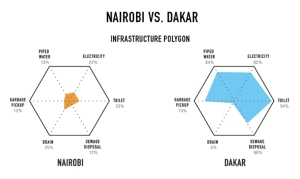

This year at the NAIS (National Association of Independent Schools) Annual Conference 2014, I unveiled some of the data visualizations that we are starting to build from our pedagography at Mount Vernon. Grant Lichtman and I partnered for a session that explored Zero-Based Strategic Thinking and practices such as pedagography that can be utilized in such self-study as a school learning community.

Chip Houston, Shelley Clifford, and I are already planning to devote an entire session at next year’s NAIS Annual Conference to the practice of instructional rounds and pedagography (provided our proposal gets accepted).

Recently, Houston, Clifford, Nicole Martin, and I spent time digging into the aggregate data that we have collected from 350 ethnographic visits and observations across two divisions. In the near future, we’ll reveal more about what we are learning from these mappings of our teaching and learning ecosystem.

Using External Visitors, Too

During this academic year, Mount Vernon has hosted over 40 schools for visits to our campus. Early on, we realized the incredible advantages and benefits to inviting our visitors on learning walks with us. As a final leg of these host-visitor learning walks, we debrief the visit using such visible thinking routines as “See-Think-Wonder” and “Rose-Thorns-Buds.” The insights provided by our visitors are proving invaluable as we compare and contrast what they observe and share with our own archives from instructional rounds.

- “Fourteen Schools Visit Mount Vernon” news story from most recent April 3 Visit Day

- Storify Tweet Archive: “.@MVPSchool Hosts 14-School Learning Walk”

More to Come – A Mea Culpa

Reading back through this post, I realize how incomplete it is as a true record of the incredible work that the Middle School and Lower School leaders have been engaging to study our school and develop our learning community. However, I’ve been about to burst at the seams to start telling the story here, so I hope you’ll forgive the errors of omission committed by me in my excitement. Any gaps are the fault of my writing and not the fault of the incredible professionals forwarding this work —

Chip Houston, Katie Jones, Shelley Clifford, Nicole Martin, Mary Cantwell, the Middle School Heads of Grade, the Middle School IR Network Group, the Lower School Heads of Grade, Emily Breite, Kelly Kelly, and a number of others who support our work.

We look forward to sharing more of the well with you as we continue to innovate around professional learning and practice at Mount Vernon Presbyterian School and the Mount Vernon Institute for Innovation.